|

Understanding the dangers of box jellyfish and Irukandji syndrome

Box jellyfish venom is deadlier than a cobra's

By Isabel M. Algaze Gonzalez, MD

At about 6 a.m. 37-year-old Angel Yanagihara went for a long swim off the shore of Kaimana Beach, Oahu, Hawaii. Along the way, she was stung by a spawning aggregation of bx jellyfish. Dozens of nearly transparent tentacles wrapped around her neck, arms and ankles. Her breathing took conscious effort and the pain became almost unbearable. As an experienced swimmer and diver, she knew that it was imperative to keep calm to prevent drowning, but she found herself wheezing, her muscles weakening and felt pain radiating throughout her body. She managed the taxing swim back to shore then collapsed. Days later she would discover that little was known about the culprit jellyfish species and even less about the composition of its venom. Little did these animals know that they inspired a worthy adversary.

Jellyfish are among the most primitive animal groups. Their fossils appeared 550 million years ago in the Cambrian period (Ruppert and Barnes, 1994). Although they have a simple tow-layer tissue organization, and lack a brain, we know that indeed they have eyes — 24 to be exact (Zbynek et al, 2008). Although they have been here for millions of years, information about these creatures and their impact on the economy and human health is scarce. As a class, cubozoans (box jellies) have the most dangerous venom in the world. They are even deadlier than cobras (Brinkman, 2015). Box jellyfish sting symptoms are venom-dose dependent and range from mild local pain to death. Their sting can also cause Irukandji syndrome, which causes a complex sequela of symptoms that could manifest as hypertension with later hypotension, trembling and extreme pain. Pulmonary edema or intracranial hemorrhage are also possible (Yanagihara et al 2016).

Common misconceptions abound, including the assumption that Irukandji syndrome is caused by only one species of box jellyfish, and that it is an exotic faraway entity found only in Australia. However, case reports document that several different box jellyfish species can cause Irukandji syndrome, including Alatina alata, a species endemic to U.S. waters in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Florida and Guam. Its incidence and prevalence is misdiagnosed (commonly as an allergic reaction or drowning), underreported and improperly treated. Even in places where the syndrome has been reported (Up to now: Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Florida) or where box jellyfish have been described (Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Texas, Louisiana, Florida, North Carolina, New Jersey and California), most clinicians do not know of their existence. Many strongly doubt the possibility that one of their patients could have Irukandji syndrome.

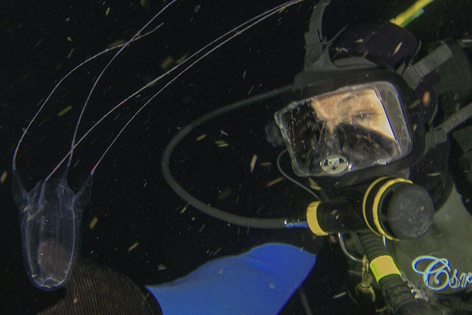

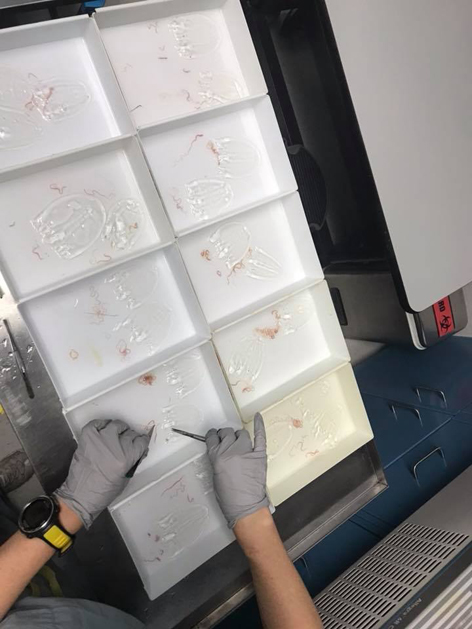

Yanagihara, a student of biochemistry, cell and neurobiology, was stung just two weeks before her doctoral graduation. After a quick survey of the literature and no satisfactory description of the biochemical composition of these venoms, she quickly wrote a proposal to do such studies. To her great surprise, that proposal was funded and the grant redirected her career path toward box jellyfish research. Her research ranges from studies of cubozoan venom biochemistry to basic field ecology. Over the last 20 years, her field efforts in Hawaii have resulted in the longest continuous census data series in the world, as she has recorded monthly influx counts of the Alatina alata population in Hawaii. She personally gets up at 2 a.m. to catch jellyfish with special protective equipment. She also accompanied author and long-distance swimmer Diana Nyad from dusk to dawn in her swim from Cuba to Miami as her safety freediver. Their issue was not sharks, climate or perseverance, but box jellyfish, which prevented Diana from completing this feat in three of her five attempts.

Yanagihara reports that thebox jellyfish venom induces pathogenic sequelae resembling more of a sepsis type of shock. Although it mimics an allergic reaction, there is no true IgE mediated immunity other than a direct venom-induced release of histamine and cytokines caused by specific pore forming toxins that are structurally similar to pathogenic bacterial porins (Yanagihara et al 2016; Jouiaei et al, 2015). She proposes that the mechanism is venom porin driven in which “perforated” cells spill out storage contents and account for an acute catecholamine surge due to ruptured platelets and later cytokine excess from perforated white blood cells (Yanagihara et al, 2016). Because this process is not IgE mediated, classical hymenoptera sting treatment paradigms are not suitable. The well-intentioned administration of epinephrine in the setting of jellyfish sting presentation with catecholamine surge could lead to end-organ failure. Currently, the best evidence-based information supports two-step first aid: 1) prevent activation of the undischarged venom filled nematocysts left on the skin after tentacle contact and 2) soak the affected area in 42-45oC water (or apply a hot pack) for 20-45 min to specifically heat inactivate venom already deposited into the sting-site tissues. Do not rinse with fresh water, cold water, urine, alcoholic drinks or rubbing alcohol. Do not apply pressure or ice. Do not scrape with a credit card, shave with shaving cream or rub with sand (Yanagihara et al, 2016; Yanagihara and Wilcox, 2016; Yanagihara and Wilcox, 2017; Wilcox et al, 2017; Doyle et al, 2017).

As time goes by we see more reports about jellyfish sightings and stings, including a weekend in June 2018, when Florida lifeguards treated more than 800 jellyfish stings. (USA Today, 2018). A 2012 study concluded that populations of jellyfish are increasing in the seas and along coastal areas (Brotz et al, 2012). This may be due to climate change as well as human interference. There are many places in the world where people die often from these stings due a lack or delay of medical care.

Yanagihara has traveled to Australia, Indonesia and lately to the Philippines, where she is working on public health outreach focused on education, prevention and mitigation of sting injuries. In Thailand, she is a U.S. State Department Fulbright Specialist. Department of Defense funding led to the development of a rapid-acting, two-step topical spray and cream for use by combat divers; in keeping with the funding requirements, they are now fully commercialized and available “over the counter.” She has stung herself numerous times and donated her blood in studies focused on understanding these amazing creatures. In addition, she tests venom inhibitors and sting preventatives. The commercialized two-step patented first-aid products are currently being compared with conventional approaches, including vinegar dousing followed by hot or cold packs in a clinical trial. Yanagihara urges doctors to learn about Irukandji syndrome and treat it with the latest recommendations.

Additional Photos

References

- Ruppert, E. E. and R. D. Barnes. Invertebrate Zoology. 6th edition. 1994. Saunders. Ft Worth, TX.

- Kozmik Z., Ruzickova J., Jonasova K., Matsumoto Y., Vopalensky P. , Kozmikova I., Strnad H., Kawamura, S., Piatigorsky. J., Paces, V. , Vlcek, C.. Assembly of the cnidarian camera-type eye from vertebrate-like components. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Jul 2008, 105 (26) 8989-8993.

- Brinkman, D., Jia, X., Potriquet, J., Kumar, D., Dash, D., Kvaskoff , D.and Mulvenna, J.. Transcriptome and venom proteome of the box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri. BMC Genomics 2015, 16:407.

- Yanagihara, A.A., Wilcox, C., Smith, J., Surrett, G.W. Cubozoan envenomations: Clinical features, pathophysiology and management. In: Goffredo, S., Dubinsky, Z., editors, The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future. The world of Medusa and her sisters., 1st ed. 2016, 637-652.

- Jouiaei, M.; Yanagihara, A.A.; Madio, B.; Nevalainen, T.J.; Alewood, P.F.; Fry, B.G. Ancient Venom Systems: A Review on Cnidaria Toxins. Toxins 2015, 7, 2251-2271.

- Yanagihara, A.A., Wilcox, C., King, R., Hurwitz, K., Castelfranco, A.M. Experimental assays to assess the efficacy of vinegar and other topical first-aid approaches on cubozoan (Alatina alata) tentacle firing and venom toxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2016;8(1).

- Wilcox, C.L., Yanagihara, A.A. Heated debates: hot-water immersion or ice packs as first aid for cnidarian envenomations? Toxins (Basel). 2016 Apr 1;8(4):97.

- Wilcox, C.L., Yanagihara, A.A Evaluating First-Aid Reponses To Cnidarian Stings: A Critical Review Of The Literature And A Novel Assay Array To Standardize Testing Toxicon 2016,119:372 -373.

- Yanagihara AA, Wilcox CL, Cubozoan Sting-Site Seawater Rinse, Scraping, and Ice Can Increase Venom Load: Upending Current First Aid Recommendations Toxins 2017, 9(3), 105.

- Wilcox CL, Headlam JL, Doyle, TK, Yanagihara AA, Assessing the Efficacy of First-Aid Measures in Physalia sp. Envenomation, Using Solution- and Blood Agarose-Based Models, Toxins, 01 April 2017, Vol.9(5), 49.

- Doyle TK, Headlam JL, Wilcox CL, Macloughlin E, Yanagihara AA, Evaluation of Cyanea capillata Sting Management Protocols Using Ex Vivo and In Vitro Envenomation Models, Toxins, 01 July 2017, Vol.9(7), 215.

- N'dea Yancey-Bragg, Florida lifeguards treat more than 800 for jellyfish stings. Here's what to do if you get stung. USA Today, June 12, 2018, Retrieved from: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2018/06/12/600-jellyfish-stings-florida/694679002/

- Brotz, L., Cheung, W., Kleisner, K., Pakhomov, E., Pauly, D. Increasing jellyfish populations: Trends in Large Marine Ecosystems. Hydrobiologia.2012, 690. 3-20.